Trends and determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption in Peru: A national survey analysis from 2016 to 2022

Research Article - (2023) Volume 43, Issue 2

Received: 05-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. CNHD-23-109409; Editor assigned: 07-Aug-2023, Pre QC No. CNHD-23-109409 (PQ); Reviewed: 21-Aug-2023, QC No. CNHD-23-109409; Revised: 28-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. CNHD-23-109409 (R); Published: 04-Sep-2023, DOI: 10.12873/0211-6057.43.02.201

Abstract

Introduction: The intake of five or more servings of fruits and/or vegetables is recommended for the prevention of various diseases. However, the level of consumption has varied over time.

Objective: This study analyzed the trend in fruit and vegetable consumption in Peru from 2016 to 2022 and explored associated factors.

Materials and Methods: A secondary data analysis of the Peru Demographic and Health Survey (ENDES) was conducted, calculating adjusted Prevalence Ratios (aPR) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI95%).

Results: The trend in consumption saw a significant decrease in 2020. In the regression analysis, associations were found with being male (aPR=1.23; CI95% 1.18-1.27); being between 26 to 59 years old (aPR=0.80; CI95% 0.77-0.83), between 60 to 69 years old (aPR=0.78; CI95% 0.72-0.85) and 70 years or older (aPR=0.75; CI95% 0.67-0.83); the year 2020 (aPR=0.58; CI95% 0.54-0.63) and 2021 (aPR=0.88; CI95% 0.83-0.94); having a partner (aPR=0.58; CI95% 0.54-0.63); living on the coast (aPR=0.87; CI95% 0.83-0.91), in the highlands (aPR=0.74; CI95% 0.70-0.78) and in the jungle (aPR: 0.93; CI95% 0.88-0.98); being poor (aPR=1.13; CI95% 1.06 -1.21) and of middle status (aPR=1.10; CI95% 1.02-1.18); smoking daily (aPR=0.78; CI95% 0.67-0.89); drinking alcohol (aPR=1.12; CI95% 1.07-1.17) and having T2DM (aPR=1.26; CI95% 1.15-1.38).

Conclusion: Consumption has varied over the years, with a decrease in 2020. Associated factors include being male, having T2DM, and drinking alcohol. Additionally, having a partner, living on the coast, in the highlands or in the jungle, being poor or of middle status, and smoking daily were associated with lower consumption.

Keywords

Fruit, Vegetables, Epidemiologic factors, Public health.

Introduction

The eating of fruits and greens has been conclusively identified for its health advantages [1]. However, inadequate intake is common all over, resulting in a worldwide health crisis [2]. Nutrition that ideally incorporates fruits and greens has been shown to have a positive effect in preventing non-communicable sicknesses, an increasingly pressing issue for health methods [3].

In Latin America along with the rest of the planet, the use of fruits and veggies has declined [4]. This has been more recognizable during the COVID-19 global pandemic [5]. The consumption of fruits, lean proteins, grains, and dairy goods, in line with current analysis, substantially fell, while the intake of sugars, fats, and sweets significantly increased during the pandemic [6].

In Peru, until now, few reports have been developed in which the tendencies and aspects related to the intake of greens and fruits have been examined. Therefore, this work targeted to analyze this hole in the literature, for which data from the National Demographic and Health Survey (ENDES) were utilized to explore the tendency in the consumption of fruits and vegetables in Peru from 2016 to 2022. Also, the variables connected with the consumption of fruits and vegetables were investigated, with the aim of recognizing likely areas of intervention and thus improving the diet and health of Peruvians.

The findings of this research have the potential to profoundly impact the shaping of public health policies and health promotion initiatives within the nation going forward. By obtaining a better understanding of the tendencies and factors linked to the intake of fruits and vegetables, more powerful strategies can be applied to encourage nutritious eating habits and move towards the avoidance of non-communicable illnesses in individuals of Peru.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This constitutes an investigating, cross-sectional analysis, based on in advance obtainable data from ENDES [7]. A two-stage stratified example design was utilized to confirm the representativeness of the specimen at the nationwide level. The information originates from 2016 to 2022, which were analyzed as per the Strengthening the Posting of Observational reports in Epidemiology (STROBE) rules for observational investigation [8].

Population and sample

The ENDES is representative at the national level. The sample was selected, for which a balanced, stratified, and independent probabilistic sampling design was used, at the departmental level and by rural and urban area. At each stage, the sampling units were randomly selected, and non-responses and missing data were handled using optimal imputation techniques to preserve the representativeness of the sample. It should be noted that people with incomplete or inconsistent data from the variable of interest were discarded.

Definition of variables

The first outcome variable was fruit consumption, which was evaluated through the question: How many portions of fruit did you consume daily? Then, it was formulated whether they consumed less than five servings a day compared to five or more. Vegetable intake was the second outcome variable. This was evaluated with the following question: How many portions of vegetable did you eat daily? Subsequently, it was categorized into whether they consumed less than five servings a day versus five or more. The decision of the cut-off points was according to the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation [9].

The factors to be evaluated were sex (male versus female), age categorized (15–34, 35–60, 61–69, and ≥ 70 years), marital status (with partner, without partner), educational level (primary, secondary, and higher), wealth index (poor, middle, rich, and richest), natural region (Metropolitan Lima, rest of the coast, highlands, and jungle), daily tobacco consumption (yes versus no), selfreported alcohol intake in the previous 12 months (yes versus no), year (from 2016 to 2022), Body Mass Index (BMI) (normal weight, overweight, and obesity), history of arterial hypertension (yes versus no), and history of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). The way each variable was measured can be reviewed in the ENDES report [7].

Statistical analysis

The analysis was developed with the statistical software STATA 17. Descriptive variables were shown in absolute and relative frequencies. The factors for evaluation were presented bivariately, and crude Prevalence Ratios (RPc) and adjusted (RPa) were calculated with their respective confidence intervals, at 95% (CI95%), for which generalized linear models with robust variance estimation were used; a Poisson distribution with logarithmic link functions was assumed.

To measure whether the effects of the associated factors vary according to the variables already mentioned, stratified analyses were carried out. Likewise, a trend analysis was carried out over time to identify whether the prevalence of fruit and vegetable consumption has changed over the years. The analyses were developed, for which it was considered that they were complex samples.

Ethical aspect

This manuscript was based on an analysis of public domain survey data sets and freely available online, with all identifier data removed; the downloaded information was presented anonymously, so the possible harms to the people in the primary study were minimal.

Results

The sample is 247,857 people, of which 51.50% were women. 32.31% had a higher level of education; 78.35% lived in urban areas; the majority did not smoke daily (98.51%) and did not drink alcohol (88.28%); 24.30% were obese; 9.52% of the participants reported having a history of arterial hypertension and 3.98% had type 2 diabetes mellitus. Regarding the intake of fruits and vegetables, only 9.00% reported consuming five or more servings daily. This proportion remained relatively stable over the years, with the exception of a significant decrease in 2020. The rest of the results can be seen in Table 1.

| Characteristic | n=247,857 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 127,653 (51.50%) |

| Male | 120,204 (48.50%) |

| Group age | |

| 15 to 35 years old | 106,800 (43.09%) |

| 36 to 59 years old | 99,845 (40.28%) |

| 60 to 69 years old | 22,093 (8.91%) |

| 70 years to more | 19,119 (7.71%) |

| Year | |

| 2016 | 35,508 (14.33%) |

| 2017 | 35,649 (14.38%) |

| 2018 | 35,450 (14.32%) |

| 2019 | 35,296 (14.24%) |

| 2020 | 34,027 (13.73%) |

| 2021 | 35,695 (14.40%) |

| 2022 | 36,182 (14.60%) |

| Educational Level | |

| No Level | 461 (0.23%) |

| Primary | 42,229 (20.97%) |

| Secondary | 93,653 (46.50%) |

| Superior | 65,073 (32.31%) |

| Civil status | |

| Single | 82,474 (33.27%) |

| With a partner | 165,384 (66.73%) |

| Natural region | |

| Metropolitan Lima | 70,767 (28.55%) |

| Resy of coast | 75,555 (30.48%) |

| Montain Range | 66,777 (26.94%) |

| Jungle | 34,759 (14.02%) |

| Area of residence | |

| Urban | 194,207 (78.35%) |

| Rural | 53,650 (21.65%) |

| Wealth index | |

| The poorest | 33,917 (17.53%) |

| Poor | 40,934 (21.16%) |

| Medium | 41,200 (21.29%) |

| Rich | 39,956 (20.65%) |

| Richest | 37,486 (19.37%) |

| Daily smoking | |

| No | 244,175 (98.51%) |

| Yes | 3,682 (1.49%) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| No | 218,677 (88.28%) |

| Yes | 29,043 (11.72%) |

| Body mass index | |

| Normal Weight | 73,572 (36.63%) |

| Overweight | 78,474 (39.07%) |

| Obesity | 48,809 (24.30%) |

| History of hypertension arterial | |

| No | 224,095 (90.48%) |

| Yes | 23,589 (9.52%) |

| History of T2DM | |

| No | 237,863 (96.02%) |

| Yes | 9,865 (3.98%) |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption ≥ 5 servings per day | |

| No | 225,560 (91.00%) |

| Yes | 22,297 (9.00%) |

A statistically significant association was found with consuming five or more servings per day with being male (aPR: 1.23; 95% CI 1.18, 1.27) versus being female, in the multivariable regression analysis; being between 26 to 59 years old (aPR: 0.80; 95% CI 0.77, 0.83), between 60 to 69 years old (aPR: 0.78; 95% CI 0.72, 0.85) and 70 years or older (aPR: 0.75; 95% CI 0.67, 0.83) compared to being 15 to 35 years old; the year 2020 (aPR: 0.58; 95% CI 0.54, 0.63) and the year 2021 (aPR: 0.88; 95% CI 0.83, 0.94); having a partner (aPR: 0.58; 95% CI 0.54, 0.63); living in the coast (aPR: 0.87; 95% CI 0.83, 0.91), highlands (aPR: 0.74; 95% CI 0.70, 0.78) and jungle (aPR: 0.93; 95% CI 0.88, 0.98); being poor (aPR: 1.13; 95% CI 1.06, 1.21) and middle class (aPR: 1.10; 95% CI 1.02, 1.18); being a daily smoker (aPR: 0.78; 95% CI 0.67, 0.89); drinking alcohol (aPR: 1.12; 95% CI 1.07, 1.17) and having T2DM (aPR: 1.26; 95% CI 1.15, 1.38) (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Fruit and vegetable consumption ≥ 5 servings per day | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n = 225,560 | Yes, n = 22,297 | cPR | 95% CI | aPR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 117,547 (92.08%) | 10,106 (7.92%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Male | 108,013 (89.86%) | 12,191 (10.14%) | 1.31 | 1.27, 1.35 | 1.23 | 1.18, 1.27 |

| Group age | ||||||

| 15 to 35 years old | 95,283 (89.22%) | 11,516.93 (10.78%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 36 to 59 years old | 91,703 (91.85%) | 8,141.46 (8.15%) | 0.81 | 0.78, 0.83 | 0.8 | 0.77, 0.83 |

| 60 to 69 years old | 20,548 (93.01%) | 1,544.86 (6.99%) | 0.69 | 0.65, 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.72, 0.85 |

| 70 years to more | 18,026 (94.28%) | 1,093.63 (5.72%) | 0.5 | 0.46, 0.54 | 0.75 | 0.67, 0.83 |

| Year | ||||||

| 2016 | 31,964.46 (90.02%) | 3,543.73 (9.98%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 2017 | 32,172.21 (90.25%) | 3,477.33 (9.75%) | 0.98 | 0.93, 1.03 | 0.97 | 0.90, 1.04 |

| 2018 | 32,054.58 (90.29%) | 3,445.29 (9.71%) | 0.93 | 0.89, 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.91, 1.05 |

| 2019 | 31,874.18 (90.31%) | 3,421.32 (9.69%) | 0.89 | 0.85, 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.88, 1.00 |

| 2020 | 32,483.41 (95.46%) | 1,544.13 (4.54%) | 0.44 | 0.41, 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.54, 0.63 |

| 2021 | 32,398.46 (90.77%) | 3,296.07 (9.23%) | 0.89 | 0.85, 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.83, 0.94 |

| 2022 | 32,613.19 (90.14%) | 3,569.01 (9.86%) | 0.98 | 0.93, 1.03 | 0.94 | 0.88, 1.00 |

| Educational Level | ||||||

| No Level | 435.97 (94.52%) | 25.27 (5.48%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Primary | 39,587.38 (93.74%) | 2,641.97 (6.26%) | 1.28 | 0.85, 2.06 | 0.97 | 0.60, 1.70 |

| Secondary | 84,221.80 (89.93%) | 9,431.41 (10.07%) | 1.88 | 1.25, 3.01 | 1.23 | 0.76, 2.17 |

| Superior | 58,760.70 (90.30%) | 6,312.61 (9.70%) | 1.86 | 1.24, 2.99 | 1.21 | 0.75, 2.13 |

| Civil status | ||||||

| Single | 73,605.76 (89.25%) | 8,868.07 (10.75%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| With a partner | 151,954.72 (91.88%) | 13,428.81 (8.12%) | 0.78 | 0.75, 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.83, 0.90 |

| Natural region | ||||||

| Metropolitan Lima | 63,344.78 (89.51%) | 7,422.71 (10.49%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Resy of coast | 68,835.63 (91.11%) | 6,718.95 (8.89%) | 0.81 | 0.77, 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.83, 0.91 |

| Montain Range | 61,982.36 (92.82%) | 4,794.28 (7.18%) | 0.68 | 0.65, 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.70, 0.78 |

| Jungle | 31,397.71 (90.33%) | 3,360.93 (9.67%) | 0.89 | 0.84, 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.88, 0.98 |

| Area of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 175,872.07 (90.56%) | 18,334.82 (9.44%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Rural | 49,688.41 (92.62%) | 3,962.05 (7.38%) | 0.84 | 0.82, 0.87 | 1.03 | 0.96, 1.10 |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| The poorest | 31,363.70 (92.47%) | 2,552.89 (7.53%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Poor | 37,016.56 (90.43%) | 3,917.40 (9.57%) | 1.17 | 1.12, 1.22 | 1.13 | 1.06, 1.21 |

| Medium | 37,172.36 (90.22%) | 4,027.81 (9.78%) | 1.21 | 1.16, 1.27 | 1.1 | 1.02, 1.18 |

| Rich | 36,158.82 (90.50%) | 3,797.50 (9.50%) | 1.24 | 1.18, 1.31 | 1.03 | 0.95, 1.11 |

| Richest | 33,950.05 (90.57%) | 3,535.60 (9.43%) | 1.22 | 1.16, 1.30 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.07 |

| Daily smoking | ||||||

| No | 222,223.16 (91.01%) | 21,952.29 (8.99%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 3,337.32 (90.64%) | 344.59 (9.36%) | 1.17 | 1.04, 1.32 | 0.78 | 0.67, 0.89 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| No | 199,688.63 (91.32%) | 18,988.15 (8.68%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 25,747.13 (88.65%) | 3,295.41 (11.35%) | 1.39 | 1.33, 1.45 | 1.12 | 1.07, 1.17 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Normal Weight | 66,407.74 (90.26%) | 7,164.60 (9.74%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Overweight | 71,477.57 (91.08%) | 6,996.16 (8.92%) | 0.94 | 0.91, 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.94, 1.01 |

| Obesity | 44,296.16 (90.75%) | 4,512.82 (9.25%) | 0.97 | 0.93, 1.02 | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.07 |

| History of hypertension arterial | ||||||

| No | 203,680.12 (90.89%) | 20,414.42 (9.11%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 21,717.29 (92.06%) | 1,872.01 (7.94%) | 0.93 | 0.88, 0.98 | 1.06 | 0.99, 1.14 |

| History of T2DM | ||||||

| No | 216,475.51 (91.01%) | 21,387.36 (8.99%) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 8,960.02 (90.82%) | 905.28 (9.18%) | 1.01 | 0.92, 1.09 | 1.26 | 1.15, 1.38 |

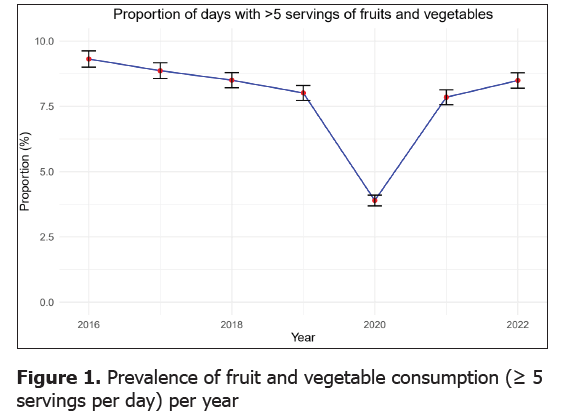

In Figure 1, the phenomenon in the intake of fruits and veggies (five or a lot of serving’s everyday time) in Peru, from 2016 to 2022, is observed. In 2016, 9.98% of the citizens announced taking in five or a lot of servings daily time. This proportion decreased marginally in the subsequent ages, with 9.75% in 2017; 9.71% in 2018, and 9.69% in 2019. In 2020, a substantial reduce in the intake of fruits and vegetables was observed, with merely 4.54%; in 2021, it increased again to 9.23% and in 2022, this proportion rose even further to 9.86% and approached the levels observed before the pandemic.

Discussion

Trend in the consumption of fruits and vegetables

This research shows a shocking surge in the quantity of fruits and vegetables consumed in Peru from 2016 up till the present year 2022. Though for most of that time percentage of individuals eating 5 or more helpings of citrus fruit and vegetables daily lingered at about 9% to 10%, the preposition was utilized to indicate location inside. 2020, there was a considerable decline, accompanied by an increase in 2021 and 2022. This example may mirror the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating propensities. Recent studies have illuminated different changes in eating designs over the span of the pandemic, for instance, lessening in the utilization of vegetables and organic product, as indicated by examinations as indicated by investigations [10,11]. Likewise, it is seen that isolation affected the eating designs and way of life of understudies and specialists in the food science field [12]. These findings support the idea that the COVID-19 pandemic could have had a significant effect on the utilization of organic products and vegetables in Peru.

The drop in people taking in greens and fruits is noticeable and likely demonstrates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the year 2020. The pandemic has caused disruptions to food structures in their entirety as well as has interrupted supply networks; as a result, it has hampered reach to fresh and nutritionally rich meals like the yield of gardens and orchards [13]. The reduction in consumption of fruits and vegetables all through the pandemic years symbolizes an occurrence far from exclusive to Peru as there has in the same way been a decline in global partaking of such nutritious victuals within an identical timeframe [14]. However, it is heartening to think the routine switched in 2021 and 2022, signifying a recovery in the intake of fruits in the country.

Factors associated with the consumption of fruits and vegetables

The research uncovered that males ate more veggies and produce compared to females as it was linked to being a man or female. That closing result matches what came previously. For example, a study that included Kuwait found that guys ate more veggies and fruits each day than women [15]. In a similar way, a study performed in 49 lower and middle-income nations found that males followed guidelines for fruit and vegetable intake to more of an extent than females did [16]. However, research in Sweden found that women consumed more unfried vegetables than men [17]. Those findings emphasize the value of thinking of sex when arranging and performing ways to promote the eating of veggies and fruits.

Our results indicate a major connection between time and eating greens and produce. Specifically, it demonstrated that being amidst 26 to 59 years of age, 60 to 69 years of age, and 70 years or more contrasts from being amidst 15 to 35 years of age. This outcome matches earlier research. This showed that intake reduced as time passed. In a lifelong study in Finland, the result revealed that physical work along with the uptake of greens and produce from childhood to midlife, likely, go together [18]. Added study within the United States established that the consumption of produce was found to be less among younger persons in comparison to older persons [19]. In a similar manner, a German study found that intake of produce diverged dependent on sexual sort, age, BMI, and socioeconomic level [20]. The discoveries highlight the significance of health promotion interventions aimed towards motivating the intake of vegetables and fruits at all ages, but especially amongst the youngest, in boosting intake.

The fact that you were wed at the alike time became a deciding element in using fruits and greens. During our exploration, it was perceived that having a partner contributed to a reduced probability of consuming 5 or more helpings of fruits and vegetables every day when holding the lack of a spouse as the thing compared. This finding goes with previous research displaying that hitched or joined persons eat less healthily compared to singles [21,22]. It is likely that shared tasks and family relationships impact food selections, which can result in a reduced usage of fruits and vegetables [23]. However, one must recognize that such outcomes are probable to vary depending on the prevailing cultural and financial environment. In this regard, more study is necessary to identify those connections more precisely.

Regarding geographical area, the findings match up with the preceding study, which highlighted modifications in result based on place’s spot [24,25]. The reasons for such variations can be attributed to things like the supply and availability of vegetables and fruits, which can vary by place [26]. For example, in more distant or mountainous areas, there can be less access to marketplaces or shops that sell these fresh products. Likewise, cultural aspects must be thought of, as eating habits and food preferences could differ by district [27]. So, further inquiry is fundamental to comprehend such regional variations more precisely and how they can be tackled to boost the intake of veggies and fruits.

In the part that follows, the relationship between social position and expenditure of greens and fruits is examined. The findings of this document reveal that being in a needy situation and having a moderate position in society was joined with greater use of fruits and vegetables. These outcomes coordinate with what has been stated, which proposes that position in society might affect eating habits, counting the expenditure of these [28-30].

For example, in a study by Assari et al., [30], it turned out that foods rich in nutrients tend to cost more, which can limit their intake among people with lower incomes. However, in our review, it came out that consumers within the lowest socioeconomic groups reported greater usage of vegetables and fruits. This may be due to cultural or availability factors that weren’t gauged in this research. Additionally, in a report done in Ghana, it turned out that socioeconomic level was positively related to dietary diversity, an indication of diet quality [29]. Those with higher socioeconomic status may partake in a wider selection of nutrition, including eating more vegetables and fruit, as evidenced by the examination. After a long period of study, the investigation conducted with American teenagers around 14 to 18 years found that a higher diet quality, calculated using the Healthy Eating Index-2010, was inversely linked to both BMI and WC while being directly connected to total cholesterol levels [28]. The research suggests that a diet including ample portions of vegetables and fruit, apart from facilitating the avoidance of weight gain, can further provide additional benefits regarding one’s wellbeing, due to supplying abundant amounts of vegetables and fruits.

The consumption of alcohol and tobacco also showed a significant association with the consumption of vegetables and fruits. The results indicated that smokers were less likely to have the effect. This result is consistent with previous studies, which have shown that smokers tend to follow less healthy diets versus non-smokers [31]. On the contrary, they found that drinking alcohol was straight connected to the usage of greens and fruits. While this conclusion could appear paradoxical at first glance, particular studies have proposed that individuals who consume alcoholic beverages in modest quantities might tend to have more healthy diets compared to those who abstain altogether [32]. Although enjoying alcohol in moderation can be acceptable, remember that overindulgence poses risks to your wellbeing. This is also true if you fail to incorporate a diet full of fruits and vegetables on a consistent basis [33].

With the assessment of the elements associated with how much farm produce and edibles persons take in, a strong connection was observed with the existence of T2DM. This outcome agrees with the writings, which propose that persons with T2DM may be more likely to follow nutritional suggestions, like consuming vegetables and produce, as a part of coping with their condition [34]. Also, in some reports it has been advised that consuming more fruits and vegetables could have a protective impact against establishing non-communicable sicknesses, like T2DM [35,36]. However, one must recognize that the connection between fruit and vegetable consumption and T2DM can go in either direction. On the one hand, higher usage may decrease the chance of developing T2DM [36]. While supplementing their diet with additional fruit and vegetable consumption could be beneficial, patients with T2DM may alternatively increase their intake of such produce as one way of managing their condition [22].

Public health importance

The results of this work have helpful effects for general health. Taking enough vegetables and fruits is a basic part of a balanced diet and has been linked with a reduced chance of some lingering sicknesses, like heart issues, sure forms of cancer, and strokes [37]. The WHO advises consuming a minimum of 400 grams of plants and fruits each day to help evade lingering health concerns such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and obesity [38].

Still, with the evident medical benefits, numerous fails to partake of the proposed amounts of vegetables and produce. Our discoveries demonstrate that definite classes of persons in Peru, such as females, more youthful individuals, and each day people, who smoke, tend to eat under five parts of vegetables and organic products on a daily reason [39].

These effects may help societal health efforts focused on increasing the consumption of vegetables and fruits in these communities. Initiatives to boost health might have to be customized to deal with the specific barriers to the intake of these foods encountered by these groupings. For instance, interventions might address the availability and price of vegetables and fruits. Additionally, ideas and info concerning the significance of a balanced diet may be presented [40].

Study limitations

Firstly, this study is based on self-reported survey data, which may lead to memory biases and the underestimation or overestimation of the consumption of vegetables and fruits. Although ENDES is a representative survey in Peru, the accuracy of the data depends on the respondents’ answers [41].

Secondly, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the inference of causal relationships, and although associations have been identified between various factors and the intake of fruits and vegetables, it cannot be established whether these factors are causes or consequences of this consumption.

Thirdly, although adjustments have been made for a number of potentially confounding factors, the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured or poorly measured variables cannot be dismissed. For example, adjustments could not be made for additional dietary factors, such as total energy consumption, which may influence the consumption of vegetables and fruits.

Conclusion

This work provides a detailed view of the trend in the intake of fruits and vegetables in Peru from 2016 to 2022, as well as the factors associated with this consumption.

The findings indicate that although the proportion of the population consuming five or more servings of vegetables and fruits daily has varied over these years: the general trend has been relatively stable, with a significant decrease in 2020, followed by a recovery in 2021 and 2022.

Factors associated with a higher consumption of fruits and vegetables include being male, having type 2 diabetes, and drinking alcohol. On the other hand, factors associated with lower consumption include having a partner, living on the coast, in the mountains or jungle, being poor or of middle status, and smoking daily. Seeing these results, it is inferred that it is necessary to apply health promotion strategies with the purpose of increasing the consumption of vegetables and fruits, especially among the identified population groups with low consumption.

It is recommended that future health promotion interventions focus on nutritional education and the promotion of healthy diets, specifically in groups that consume little. Also, it is important to conduct more research to explore the barriers and facilitators of fruit and vegetable consumption in different contexts and populations.

References

- Lehto E, Kaartinen NE, Saaksjarvi K, Mannisto S, Jallinoja P. Vegetarians and different types of meat eaters among the Finnish adult population from 2007 to 2017. Br J Nutr. 2022; 127(7): 1060-1072.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Liu X, Zhou Q, Clarke K, Younger KM, An M, Li Z, et al. Maternal feeding practices and toddlers’ fruit and vegetable consumption: Results from the DIT-Coombe hospital birth cohort in Ireland. Nutr J. 2021; 20(1): 84.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Bytyci-Katanolli A, Merten S, Kwiatkowski M, Obas K, Gerold J, Zahorka M, et al. Non-communicable disease prevention in Kosovo: quantitative and qualitative assessment of uptake and barriers of an intervention for healthier lifestyles in primary healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022; 22(1): 647.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Guerra Valencia J, Ramos W, Cruz-Ausejo L, Torres-Malca JR, Loayza-Castro JA, Zeñas-Trujillo GZ, et al. The fruit intake-adiposity paradox: Findings from a peruvian cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5): 1183.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Maharat M, Sajjadi SF, Moosavian SP. Changes in dietary habits and weight status during the COVID-19 pandemic and its association with socioeconomic status among Iranians adults. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 1080589.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Monroe-Lord L, Harrison E, Ardakani A, Duan X, Spechler L, Jeffery TD, et al. Changes in food consumption trends among american adults since the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 2023; 15(7): 1769.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Perú National institute of statistics and informatics.

- Elm EV, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke J P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2008; 22(2): 144–50.

- World Health Organization. Fruit and vegetable promotion initiative : a meeting report, 25-27/08/03. Nutrition Unit. 2003.

- Maugeri A, Barchitta M, Perticone V, Agodi A. How COVID-19 pandemic has influenced public interest in foods: a google trends analysis of italian data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20(3): 1976.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Magnano SLR, Barchitta M, Maugeri A, La Rosa MC, Giunta G, Panella M, et al. the impact of the covid-19 pandemic on dietary patterns of pregnant women: A comparison between two mother-child cohorts in sicily, Italy. Nutrients. 2022; 14(16): 3380.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Celorio-Sardà R, Comas-Basté O, Latorre-Moratalla ML, Zerón-Rugerio MF, Urpi-Sarda M, Illán-Villanueva M, et al. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on dietary habits and lifestyle of food science students and professionals from Spain. Nutrients. 2021; 13(5): 1494.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Van den Broeck G, Mardulier M, Maertens M. All that is gold does not glitter: Income and nutrition in Tanzania. Food Policy. 2021; 99: 101975.

- Allahyari MS, Marzban S, El Bilali H, Ben Hassen T. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behaviour in Iran. Heliyon. 2022; 8(11): e11337.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Alkazemi D, Salmean Y. Fruit and vegetable intake and barriers to their consumption among university students in Kuwait: A cross-sectional survey. J Environ Public Health. 2021; 2021: e9920270.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Darfour-Oduro SA, Buchner DM, Andrade JE, Grigsby-Toussaint DS. A comparative study of fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity among adolescents in 49 low-and-middle-income countries. Sci Rep. 2018; 8(1): 1623.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Vogt T, Gustafsson PE. Disparities in fruit and vegetable intake at the intersection of gender and education in northern Sweden: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutrition. 2022; 8(1): 147.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Lounassalo I, Hirvensalo M, Kankaanpaa A, Tolvanen A, Palomaki S, Salin K, et al. Associations of leisure-time physical activity trajectories with fruit and vegetable consumption from childhood to adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in young finns study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019; 16(22): 4437.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Faust E, Reedy J, Herrick K. Fruit and vegetable consumption among infants and toddlers by eating occasion in the United States, NHANES 2011–2018. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022; 6(1): 641.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Straßburg A, Krems C, Hoffmann I. Fruit and vegetable consumption assessed by three dietary assessment methods in regard to sex, age, BMI and socio economic status. Proc Nutr Soc. 2020; 79(OCE2): E511.

- Conklin AI, Forouhi NG, Surtees P, Khaw K-T, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Social relationships and healthful dietary behaviour: Evidence from over-50s in the EPIC cohort, UK. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100(100):167–75.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Eid LP, Leopoldino SAD, Oller GASA de O, Pompeo DA, Martins MA, Gueroni LPB. Factors related to self-care activities of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Esc Anna Nery. 2018; 22: e20180046.

- Vinther JL, Conklin AI, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Marital transitions and associated changes in fruit and vegetable intake: Findings from the population-based prospective EPIC-Norfolk cohort, UK. Soc Sci Med. 2016; 157: 120–126.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Griep LMO, Bentham J, Mahadevan P. Worldwide associations of fruit and vegetable supply with blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: an ecological study. BMJ Nutri Prev Health. 2023; 6(1): 28-38.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Allen CK, Assaf S, Namaste S, Benedict RK. Estimates and trends of zero vegetable or fruit consumption among children aged 6–23 months in 64 countries. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023; 3(6): e0001662.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Janda KM, Ranjit N, Salvo D, Nielsen A, Kaliszewski C, Hoelscher DM,et al. Association between Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Purchasing Behaviors, Food Insecurity Status and Geographic Food Access among a Lower-Income, Racially/Ethnically Diverse Cohort in Central Texas. Nutrients. 2022; 14(23): 5149.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Janda KM, Ranjit N, Salvo D, Hoelscher DM, Nielsen A, Casnovsky J, et al. Examining geographic food access, food insecurity, and urbanicity among diverse, low-income participants In Austin, Texas. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(9): 5108.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Mellendick K, Shanahan L, Wideman L, Calkins S, Keane S, Lovelady C. Diets rich in fruits and vegetables are associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk in adolescents. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):136.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Fottrell E, Ahmed N, Shaha SK, Jennings H, Kuddus A, Morrison J, et al. Distribution of diabetes, hypertension and non-communicable disease risk factors among adults in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Glob Health. 2018; 3(6): e000787.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Assari S, Lankarani MM. Educational attainment promotes fruit and vegetable intake for whites but not blacks. J (Basel). 2018; 1(1): 29-41.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Faith MS, Dennison BA, Edmunds LS, Stratton HH. Fruit juice intake predicts increased adiposity gain in children from low-income families: weight status-by-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2006; 118(5): 2066-2075.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Moghaddam E, Vogt JA, Wolever TM. The effects of fat and protein on glycemic responses in nondiabetic humans vary with waist circumference, fasting plasma insulin and dietary fiber intake. J Nutr. 2006; 136(10): 2506-11.

- Bellisle F, Hébel P, Fourniret A, Sauvage E. Consumption of 100% pure fruit juice and dietary quality in French adults: analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey in the context of the WHO recommended limitation of free sugars. Nutrients. 2018; 10(4): 459.

- Gomes-Neto AW, Osté MC, Sotomayor CG, vd Berg E, Geleijnse JM, Gans RO, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of posttransplantation diabetes in renal transplant recipients. Diabetes Care. 2019; 42(9): 1645-1652.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Lapuente M, Estruch R, Shahbaz M, Casas R. Relation of fruits and vegetables with major cardiometabolic risk factors, markers of oxidation, and inflammation. Nutrients. 2019; 11(10): 2381.

- Halvorsen RE, Elvestad M, Molin M, Aune D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 2021; 4(2): 519.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, Fadnes LT, Keum N, Norat T, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(3): 1029-1056.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a WHO-FAO expert consultation. WHO technical report series. 2003; 149.

- Miller V, Mente A, Dehghan M, Rangarajan S, Zhang X, Swaminathan S, et al. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2017; 390(10107):2037-2049.

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The lancet. 2019; 393(10184):1958-1972.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016; 9:211-217.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

Author Info

Víctor JUAN VERA-PONCE1*, Andrea P RAMIREZ-ORTEGA1, Joan A LOAYZA-CASTRO1, Gianella ZULEMA ZENAS-TRUJILLO1, Luciana SOFIA GALVEZ-LUNA1, Fiorella E ZUZUNAGA-MONTOYA2, Luisa ERIKA MILAGROS VASQUEZ ROMERO1, Rosa ANGELICA GARCIA LARA1, Jenny RAQUEL TORRES-MALCA1, Cori RAQUEL ITURREGUI PAUCAR3, Mario J VALLADARES- GARRIDO4,5 and Jhony A De La CRUZ-VARGAS12Department of Medicine, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Peru

3Department of Medicine, Universidad Tecnológica del Perú, Lima, Peru

4Department of Medicine, Universidad Continental Lima, Peru

5Department of Epidemiology, Hospital Regional Lambayeque, Chiclayo, Peru

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Google Scholar citation report

Citations : 2439

Clinical Nutrition and Hospital Dietetics received 2439 citations as per google scholar report

Indexed In

- Google Scholar

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- ResearchBible

- SCOPUS

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Access to Global Online Research in Agriculture (AGORA)

- Electronic Journals Library

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- SWB online catalog

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- MIAR

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Web of Science

Journal Highlights

- Blood Glucose

- Dietary Supplements

- Cholesterol, Dehydration

- Digestion

- Electrolytes

- Clinical Nutrition Studies

- energy balance

- Diet quality

- Clinical Nutrition and Hospital Dietetics